Translating the Past – An Interview with Runa Hino of ICU Time Travelers

Interview No. 17 highlights ID23 student activist Runa Hino, who is a member of ICU Time Travelers.

ICU Time Travelers raises awareness on the history of the internment of Japanese Americans in Japan and America (you may have seen their Instagram account). Runa does translation work and awareness raising on social media platforms.

We asked Runa about her activities in the organization, how she maintains her motivation, and the importance of student activism.

Q1. Please tell us about what you do.

I am a member of ICU Time Travelers, an organization that explores the history and accumulated knowledge of the internment of Japanese Americans by the US government during World War II. We work on material translation of primary sources from Japanese to English, and vice versa.

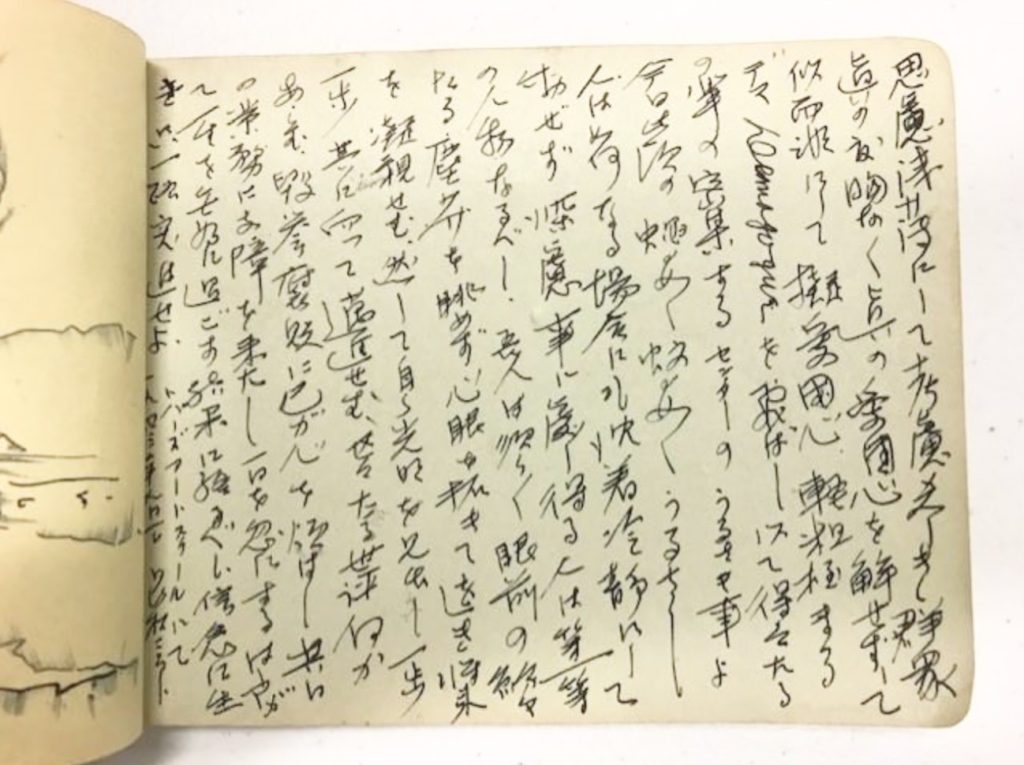

So far we have translated interviews of Japanese Americans who served in the US military during the war, and physical copies of documents found in Japanese American internment museums (often the remains of internment camps) across the US.

Q2. Some readers may not know about the internment of Japanese Americans. Can you briefly explain what happened?

The internment of Japanese Americans was the forced relocation and incarceration of Japanese Americans born and/or living in America (with Japanese ancestry/citizenship) in internment camps, and the lack of compensation for their properties by the US government during World War II. As an organization we want more people to know what happened, as it is not often taught in history classes.

Q3. When did your activities begin?

Our activities started in October 2020 as a Service Learning (SL) project called “A joint project examining the history of the internment of Japanese Americans,” in collaboration with Middlebury College in America. Our organization was founded in April 2021. We currently have 3 members, but we need more for translation work.

Q4. Why did you decide to join this project?

I couldn’t really expand my circle of friends as a freshman, and then covid hit in my second year, so I was struggling to get to know people. While searching for things I could do at ICU without physically going to campus, I found information about the SL project on ICU Portal. I decided to join because I was interested in translation/interpretation, history, and international relations. I could also obtain units unlike volunteer work, internships, or club activities.

I joined ICU Time Travelers at the invitation of a fellow SL project member, who founded the organization. Other than wanting to belong to an organization, I felt it was a waste to end this project as a one-off thing because we had just gotten to know each other and had just gotten used to the job. I felt that what we were doing was of great social importance.

Q5. Did you have any knowledge on the internment before becoming involved in the project?

I vaguely knew that this had happened, but I had never studied it in school. I had no idea that more than 120,000 Japanese Americans had been forcibly relocated and incarcerated, and I didn’t know that it was authorized by the government. I started research after deciding to join the project.

Q6. How did you feel when you first joined the project and the organization?

I didn’t initially have a strong incentive to join this SL project, so when ICU Time Travelers was founded, it was quite profound to think how far we had come.

Since entering ICU I had met a lot of student activists, and while they were very inspiring, I also felt inferior to them because I wasn’t doing anything myself. But then I joined this organization and was able to experience the joy of doing something good for society. Being able to acquire translation and intercultural communication skills is valuable as someone wanting to work in an international field in the future.

Q7. Did you have previous experience of translation? Or did it take some time to get used to?

I didn’t have any experience in translation, so at the beginning I joined study sessions and workshops taught by Part-time/Guest Associate Professor Eda and ICU graduate/translator Cathy Hirano.

Finding the most suitable translation is quite difficult – I often fix my translations based on corrections from Middlebury students and from the shared documents of other members. That way, I can see how other people translate the same phrases differently, or use different endings for the same speakers. These sorts of findings really helped me learn and grow, perhaps more than simply studying theory.

Q8. Tell us about your other activities besides translation.

Middlebury students are currently creating a website where our work will be published. We also post about ourselves and the history of the internment of Japanese Americans on Instagram, and promote these posts on Twitter. (Since Japanese American internment is a sensitive topic, we’ve decided to somewhat restrain our use of Twitter.)

We hold a couple of study sessions with Middlebury students and teachers each term, but due to the time difference and final exam periods, we haven’t been able to hold them as much as we would like to.

Q9. Why do you work with Middlebury?

I don’t know the full story, but the initial project that became the base for the SL project was proposed by a Middlebury student called Kenzo-san, who is a Japanese American. I assume he was interested in the history of the Japanese American internment and wanted to collaborate with a Japanese university, and ICU happened to be Middlebury’s partner school.

Q10. What are the advantages of working with American students on this project?

In terms of translation, we can have our work revised by native English speakers. Another advantage is increased diversity from an identity perspective: I’m Japanese, born and brought up in Japan, while other Middlebury students are American, and Kenzo-san is Japanese American.

I’m also able to meet new people. ICU’s great for building personal connections, but meeting and listening to the stories of Middlebury teachers, the front-runners of this field, and learning about various students’ research is a valuable experience.

ICU Time Travelers is actually lacking diversity. Currently our members are all ID23 and all women. Having new members of different genders, levels of study, and of various backgrounds would be more fitting for our organization, and make our work more meaningful.

Q11. What is your motivation, and how do you maintain it?

My motivation comes from the belief that what we are doing is socially significant, especially because we are able to publicly share our work. Our translations will eventually be published, not only on our website but also on the website of an American organization that interviews Japanese Americans, and will be displayed in Japanese American internment museums. It’s my first time to work on something so influential. This motivates me even when I’m busy with schoolwork and club activities.

Q12. Your slogan is “Thinking about the future by looking at the past.” In your opinion, how does your activism on Japanese American internment have the power to create a better future?

The memory of wartime will be forgotten if the younger generations don’t pass it on to future generations. We must remember the struggles of people suffering under the government’s racist strategies, while also questioning why the government undertook such measures, and why racism is still prevalent in America.

The American government used to claim that the internment was for purposes of national security – with this in mind, we must consider the balance between human rights and national security, and how a nation should protect the people’s rights when these two collide. We all have different identities and different backgrounds, and I think the world will become more and more diverse with the advancement of globalization. Having knowledge of this historical incident is bound to come in handy, especially considering that global issues are still prevalent (perhaps now even more so than during the war), such as Japan’s immigration laws.

We can’t create drastic change, but I hope our work is influential in some way. For example, if someone with slightly discriminatory/offensive ideas learns about the internment, they might reconsider their ideas and attitudes. That’s why our slogan is “Thinking about the future by looking at the past.”

I also want people to analyze such issues with an academic mindset. It is important to critically examine issues like the state of history education, racism and its solutions (the psychology of racism), problems of identity (race, religion, gender, etc.), and national security vs. human rights.

Q13. I can see why it’s important to promote your work in Japan.

Although we aim to raise awareness in both Japan and America, it’s true that we are putting more emphasis on Japan. The internment of Japanese Americans is not widely discussed in this country, even in history classes. Because of Japan’s racial imbalance, we get the sense that racism and immigration issues are still a big problem here. I hope that we can help alleviate this situation in some way, and that more people will get to know about our work.

Q14. You mentioned that having an academic mindset is important. Do you think the critical thinking skills valued in ICU should be utilized more in student activism and in society?

Yes, I think so. When people hear about such issues of racism, they tend to think it’s horrible, which it is, needless to say. But we must also consider why the government forcibly relocated and incarcerated Japanese Americans, and focus on the problem of national security.

For example, when asked whether they will swear allegiance to America during the war, most Japanese Americans said yes, because they were afraid of being put in internment camps. But some didn’t swear allegiance, even with the threat of relocation and incarceration, because they had a strong sense of their Japanese identity. Such issues of identity need to be examined from a psychological perspective. It was a terrible thing, of course, but we must always have a critical mindset.

Q15. Is the complexity and multifaceted nature of the internment something you are aware of in your activism?

I believe so. Our concern is that, if we were to post what I just talked about on social media, people would think or say that we are defending the American government, which is not the case, of course. It is undeniably an issue of racism, but it’s such a sensitive topic that we need to examine it critically – we are finding that balancing the two is quite difficult.

Q16. What is something you noticed through your activism?

ICU students are not burying their heads in the sand; in fact, many of them are interested in our work on this historical incident, but are just not willing to actively participate in it. On the flipside, this means we can get more people interested simply by being more creative with our advocacy tactics.

Q17. You mentioned that many ICU students are not willing to take part in actual activism, even if they are interested. Do you think it is important, as an activist, that students become activists?

I think it’s very important. Before entering ICU, no one around me was involved in activism, and I wasn’t particularly passionate about it either. But since becoming a university student, I’ve had friends marching in Fridays For Future demonstrations, and have met people taking part in anti-immigration law reform demonstrations while attending class. Our voices as students may not have much power, but as a member of the generation that is going to lead the world in the future, I was in awe of these people, and wanted to do something myself.

Going from doing nothing to actually becoming an activist, I think my mindset has changed a lot. Our organization may not be well-known, but I’ve realized that it’s better to take part in something, like raising awareness on the history of Japanese American internment, than to not do anything. It doesn’t matter if it’s small-scale – I hope more people will take that leap and become activists.

Q18. When do you feel a sense of accomplishment?

For me, it’s when people get to know our work and tell me that what we are doing is important, or that they are interested in it as well. I’m able to reaffirm that our work isn’t futile, that it’s meaningful. It’s empowering to think that a normal student like me can create change – this positive mindset has encouraged me to turn to other social issues and try new things.

Q19. Where do you see yourself in 10 years? Have your dreams changed since becoming a part of this project?

I’ve always been interested in international cooperation, and my dream has been to work at the UN, but through my activism I’ve started to take an interest in humanitarian aid and development. I’d never really thought about race before, but since taking part in this project, I’ve been able to think about seemingly irrelevant things like race and religion on a more personal level.

Q20. What do you have planned for the future of ICU Time Travelers?

We are currently working online, so in the future I would like to visit internment museums and let them know about us, to expand our activities. I would also like to watch films/TV series and read books on the internment of Japanese Americans.

<Find ICU Time Travelers on social media>

Instagram: @icu_time_travelers

Twitter: @ITT_ICU

Email: icu.timetravelers@gmail.com