Sarah Niehaus, an Activist Fighting and Spreading Awareness on Microplastic

Sarah Niehaus is a one year exchange student (OYR) from Germany and an activist extremely passionate about environmental issues.

ICONfront interviewed her to find out what stimulated her to conduct an exhibition on microplastic, the differences of environmental awareness between Germany and Japan, and her future plans on researching the extinction of bees.

Q1. Please tell us about your activism.

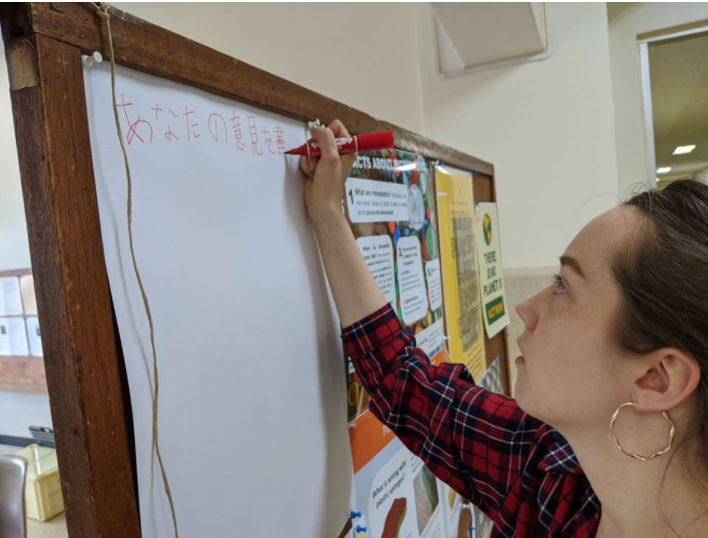

In October 2019, I started planning an exhibition about microplastics at ICU. I was able to hold the exhibition this year in February for two weeks. The exhibition included posters hung on the second floor of the main building “Honkan,” an opinion sheet to write down free thoughts and free samples of plastic-free tea bags and sponges.

I also organized an awareness-raising campaign by placing flyers with information and a mini questionnaire about micro-plastic at the university cafeteria, “Gakki.”

After the exhibition I was kindly invited by Prof. Kobayashi Makito (biology professor in ICU) as a guest speaker, to participate in his lecture about endocrine disruptors and microplastic pollution. I explained the dangers of plastic, what microplastic and nanoplastic is, the effects it has on animals and humans, and the exhibition itself.

Q2. What is the situation on plastic pollution? What is “microplastic” and “nanoplastic” and what are the effects?

Japan produces the second largest amount of plastic waste worldwide, after the USA. Awareness of the effects of plastic pollution on humans is still very low. Many people think plastic pollution does not affect humans directly. Also, many people have never heard of “microplastics” – very small pieces of plastic which are less than 5 mm. Nanoplastics are less than 1 μm (1000 nm).

There are no long-term studies about the effects of microplastic and nanoplastic on humans yet, but there have been studies on animals. WWF organized a research study to learn the effects on humans, to share facts on how we could be eating a credit card’s worth of plastic every week, which we consume through food, water and air. This includes everything made out of plastic, even tea bags made out of plastic substance. Although larger plastics can come out through feces, nanoplastics are small so they can travel through tissues, the placenta and the blood-brain barrier. Researchers predict that this can have serious physical and chemical impacts on humans, since animals studied have shown signs of liver problems and immune systems being affected.

Q3. When did you start to become interested in plastic pollution? What are the cultural differences in dealing with this global issue?

I lived in Argentina for a long time before moving back to Germany. Four years ago, at the time of my moving, there was not a lot of talk going on about microplastics and plastic pollution in Argentina. So when I went to Germany, I had given little thought to the use of plastic. My “wake-up” moment came when I went to a supermarket and wanted to buy a single-use plastic bag for my groceries. The cashier looked at me somewhat indignant and said in a very irritated voice: “Do you know that this is a VERY BIG plastic bag?”. From that moment I started to read about plastic pollution and I became passionate about the topic.

Plastic shaming is common in Germany, and if you have any plastic items, people comment on it. It is an extremely hot topic in the media and people are careful to use “my bags” and “my bottles.” In Argentina, there is less awareness than in Germany, which is why it was shocking when the cashier got angry at me since I thought staff were supposed to be kind. There is also a possibility that the country has other existential issues so that it does not have the capacity to deal with the plastic problem at the current state. Finally, in Japan, there is a stronger need for people to talk about this issue and conduct everyday activism by engaging in civilian movement, putting pressure on the media and creating laws on plastic pollution.

Q4. What was the purpose of starting your activism?

In September 2019, I interviewed ten people (including both ICU students and non-students) for a research project for my Japanese language class. The topic I had chosen was “Awareness of Plastic Waste Issues in Japan.” Although there were some interviewees that were well informed, others did not understand the impact plastic has on human beings. In Germany, I was confronted with the topic on a daily basis by the news, my family and my friends. So when I conducted the interviews and heard that in some cases there was little awareness about the issue, I immediately felt like I wanted to do something. The original plan was to create flyers and share them but eventually, I decided to take it to the next level and plan an exhibition.

Q5. How did you feel when you started?

At first I was not sure if I could do it, because I am not a biology student or a specialist; my major is Japanese studies. But then I started talking to people (professors and other activists) and researching the topic, and through this learning process I was able to do it. Of course, I am still not an expert, but I feel like I deepened my knowledge about microplastic pollution.

Q6. When do you feel empowered through your activism?

When I did the exhibition, many people contacted me, even from other universities in Tokyo. Many asked me “What can we do? We have to change something!” Receiving so much overwhelming positive feedback and realizing that many people are worried was very empowering. There was more engagement on an individual level and people took huge interest in the topic, writing comments on the opinion sheet.

Q7. What did you learn through the experience? Please share a message for ICU students!

Soon after I started planning the exhibition, I wanted to involve more people like local NGOs or individuals to make it a more inclusive project. I found many people who wanted to participate including people from overseas (Netherlands, UK, Germany) and local people: student NGOs like ByeBye Plastic Tokyo and Voice Up Japan ICU. This made me realize that there are many people passionate about environmental pollution, ready to help.

I want to tell ICU students that if you have an idea, you should just do it!! Even if you are only one person, you are able to move people and make a change. You are not alone, there is a community out there that is willing to help! You just have to take the first step! The beautiful thing is that there is a sense of community that will lend you a hand whenever you are in trouble just like I received help when I had tons of workload for the exhibition.

Also being an activist is a choice that you make and you have no reason to dedicate your entire life to it like a “do or die” situation. In Japan, activism is considered a full time job and you have to be 100% committed but there are actually many forms of activism, so it would be best to find a style that fits your lifestyle. Activism can be what YOU want it to be so it would be helpful if we can change this impression on “activism” in Japan.

Q8. Is there anything you would urge society to do? Any messages?

Many people think being an activist and trying to make a change in society is very time consuming. But I think small, everyday actions are so valuable. By talking about issues with your friends, family or posting about it on your social media now and then, you can raise awareness. I think this everyday activism can contribute to changing the narrative in society.

Q9. What would you like to do next? Any new projects or ideas?

Currently I am taking environmental studies subjects and we are discussing the decrease in the number of insects globally. I would love to do an event in Japan about the danger of the extinction of bees. Although Japanese bees are feared in Japan, many do not know the function of bees, such as how they are responsible for 30% of world wide food production. It would be great to create another exhibition project and have a discussion about it.

Instagram: @sarahbonchan